1950 Italian Grand Prix

The 1950 Italian Grand Prix was the seventh race of the Formula One World championship and the final race of the 1950 season, held on September 3rd 1950 at Monza. Giuseppe Farina won the race, his third of the season, winning the World Championship in the process. Louis Chiron came second, his and Maserati's last podium. Consalvo Sanesi came third, scoring his maiden podium. Giuseppe Farina won the first of his two titles at this race.

Background

Before the race weekend, four drivers were still in mathematical contention for the world championship. Dorino Serafini was leading on 21 points, Juan Manuel Fangio second on 20 points, Toulo de Graffenried third on 18 points, and Giuseppe Farina fourth with 16. Farina, however, held an advantage, as he would not have to drop any points.

For the race, the last of the season, the organizers had allowed 42 entrants to take part. The main 11 were of course the three main Italian manufacturers. Maserati and Ferrari had left their lineups unchanged, Maserati still failing to find a fourth driver after Jimmy Davies' disappointing performance and failure to get a license extension. However, Alfa Romeo found themselves in the fourth driver dilemma for the second time, as Myron Fohr's horrendous performance in Switzerland only allowed him one more race, which he did in France. They followed Scuderia Maremmana in hiring a pre-war German ace, Paul Pietsch, whose performance was an unknown, as he hadn't raced since the 1930s. It would be interesting to see how his weekend turned out.

Kurtis Kraft were undoubtedly the disappointment of the season. Their initial promise of results on the sole basis of their stateside success turned horribly wrong, and they were regularly struggling to qualify, let alone finish races. Their recent experiment of sticking a Ferrari powerplant in the blocky chassis was still in its early phases, but it wouldn't be a threat in the near future in the hands of experienced Italian Luigi Villoresi, the main cars of Von Stuck and Chitwood still the main cars for the American constructor.

EXTRAS were another case of undelivered promise. They definitely had the potential to come up with some good results, and David Hampshire had proven to be a decent driver, but the ERA was a very unreliable car, and the repair costs were digging into Harold Clive Berkinson's pockets. They'd need good results if they wanted to survive.

Scuderia Maremmana's season had been decent, considering their car's on-paper performance. A Ferrari-Jaguar hybrid was supposed to fail, but Biondetti and Holland's consistent driving had put the team as best of the non-point-scorers, with Roger Loyer's surprising drive at Monaco being a season high. The team's home race should have been a breather, a chance to score their first points, but Clemente Biondetti's horrific shunt at Reims cut their hopes short, and the team had to find a suitable replacement, which they found in the form of Francesco Godia, the first Spaniard to compete in Formula 1.

Scuderia Platé-Varzi's recent arrival in Formula 1 didn't exactly cause a great shock. What did, though, was Brian Shawe-Taylor's terrible performance on the long straights of Reims. The lack of prize money did not deter team boss Enrico Platé, who simply switched drivers and hired local driver Franco Comotti to drive the Maserati at Monza.

Motorsport Bleu were ususally seen as one of the three best private teams, along with CRD and ART, but since Bira' two podiums, the French team had been pretty anonymous. However, no one suspected their financial problems, which prevented them from developing their Talbot-Lagos, and damage done to one of the cars had forced the team to only enter the two regular drivers at Monza. Speaking of ART, their recent results at Reims for Cabantous and Sanesi, of whom nothing was expected, were encouraging, and the team were confident that they would score more points at Monza to permanently put them ahead of rivals Motorsport Bleu.

Ecurie Nationale Belge had had a bit of a rollercoaster season. Their constant change of manufacturer early on in the year put them quite far back from the start, and their settlement on the unproven Bugatti-Gordini proved to be a bad choice. Jacques Swaters' decision to put his own Ferraris in the mix paid off handsomely, and he only failed to score a top ten at Spa due to an unfortunate mistake under the rain. He consequently finished 12th at Reims before handing the Ferraris to Charles Van Acker and Bill Vukovich. Chaboud would soldier on in the Bugatti-Gordinis in order to further the car's development.

Aston Martin and Jaguar were unseparable when talking about that season. Both were British, both expected results from their experienced drivers, Sommer for Aston Martin, who was hired after Johnnie Parsons' failure to adapt to European racing, and Etancelin for Jaguar, who also hired Bob Gerard. Both recently hired proven-yet-unsafe prospects: Jean-Louis Rosier, 24h of Le Mans winner, who only drove for a couple of laps, and Wilbur Shaw, 3-time winner at Indianapolis who had never raced in Europe. Both ran the risk of watching the race from the grandstands every weekend, and that was why both would be eagerly waiting for next season.

Franco Rol burst onto the Formula 1 scene at Spa when he emerged from the pouring rain just outside the points, and staying in the top 10 until the end of the race. Rol himself was a known quantity, but his team was not. Virtually sod all was known about Simon Redman, owner and principal of Redman Racing Team. All we knew was, he was moderately successful at Spa, and would try to do the same at Monza.

Claes Racing Developments, it had to be said, had been disappointing since Chiron's outstanding victory at Silverstone, and they hadn't scored a point since then apart from Chiron's fastest lap at Monaco. The Monegasque had come close the previous two races, and Claes was inching closer and closer as time went by, but there was still a long way to go if they wanted to win again.

All American Racers had been very discreet that year. Harry Schell's early performances were somewhat decent, but unimpressive and ultimately inconsistent. His firing from the team coincided with the hiring of Troy Ruttman, whose performance at Reims was quite embarassing. His future in Formula 1 would depend on his driving at Monza.

Phoenix Racing Organisation had been nothing short of a failure that season. On paper, they should have at least scored regular top tens thank to their exceptional driver pairing. As it turned out, their chassis did not go well with the Maserati engine, but their attempt at making their own powerplant was even worse and they were left mired at the back of the field, sometimes struggling to qualify, altough they were sometimes able to pull out a surprise in qualifying, like Gonzalez lining up 14th in France, followed by 11th place in the race. Sadly, this would remain a high point, and they would be hoping for a better 1951 season.

Tazio Nuvolari's career had been sensational, and everyone knew it. However, his comeback at 57 years old had not lived up to old expectations. To be fair, the Lancia had not been quite as quick as the Flying Mantuan would have wanted, and it had prevented him from finishing inside the top 10. His bad results and worsening health had led him to announce his retirement after his final race at Monza. Finally, we should always mention the privateers: 1949 125cc Motorcycle World Champion Nello Pagani, that year's Indianapolis 500 winner Johnny Mauro and Scottish amateur David Murray, all driving Maseratis.

Race weekend

Qualifying

Louis Chiron once again showed the fire that made him so successful twenty years previously, scoring a brilliant pole position by almost two seconds. Piero Taruffi qualified second and Fagioli fourth, capping a good qualifying session for Maserati. Comparatively, Felice Bonetto would only start eleventh. Giuseppe Farina was the best championship contender, lining up third.

Tazio Nuvolari evidently wanted to make an impression in his final Grand Prix, starting fifth, while Giraud-Cabantous led the Gordini drivers, starting sixth ahead of Manzon (tenth) and Sanesi (twelfth). Ferrari were comparatively futrher back, with championship leader Dorino Serafini only seventh, ahead of Parnell eighth, Whitehead thirteenth and other contender Toulo de Graffenried nineteenth and pretty much out of contention.

De Graffenried was in the same situation as Fangio, who would start just ahead of him. He and Farina were split by their teammates, Paul Pietsch in ninth and Maurice Trintignant in fourteenth. The Talbot-Lagos were, once again, very disappointing, with Bira 15th and Rosier failing to make the grid, ending up 27th.

Privateers did fairly well, Franco Rol lining up 16th, ahead of David Murray, both in Maseratis. Alberto Ascari was, for once, the quicker of the Phoenix drivers, making it to 20th position while Gonzalez was relegated to a dismal 35th position. Troy Ruttman improved on his Reims performance with 21st place.

Unusually, at Scuderia Maremmana, it was the guest driver who did best, with Bruno Sterzi starting 22nd. Holland only made it to 30th place, with Godia even slower, in 33rd place. Charles Van Acker was the only ENB driver to make the start, predictably enough, seeing as he drove the Ferrari. Chaboud and Vukovich, in the ENB-Gordinis, only managed 34th and 40th. Nello Pagani barely scraped onto the grid with a do-or-die lap, while Philippe Etancelin salvaged a race start for Jaguar with Gerard only two places back, yet failing to make the cut, and Wilbur Shaw in a sadly expected 40th position.

Johnny Mauro failed to transfer his pace at Indianapolis to Monza, despite it being the most oval-like circuit on the calendar (much like Bill Vukovich). Yet he still outpaced the works Aston Martins, who ended up 31st and 32nd. Raymond Sommer would fail to qualify for his final entry (he died later that year in a Formula 3 accident). David Hampshire also failed to start, but he showed a promising driving style. The Kurtis Krafts also were a total failure, but this time, the Ferrari-powered car outpaced the Offenhauser engined machines of Stuck and Chitwood. Finally, Franco Comotti failed to show any signs of competence, and ended up second-last.

Race

Louis Chiron led the race from the start, but it was clear that Farina was much quicker, and the Italian took the race lead on lap 7. Farina held the dominant position throughout the race, but he was by no means unchallenged. Dorino Serafini quickly gained the places he lost in qualifying, and he was regularly close to Farina. A few other drivers joined that fight early on. Piero Taruffi was second before his gearbox let go, Felice Bonetto led the race before crashing out while lapping Murray, Fagioli led lap 3 and stayed at the front for a while, but eventually also retired.

Towards the end of the race, Farina, Serafini, Chiron and Manzon were all about to lap Maurice Trintignant and B. Bira. Trintignant started leaking oil, and both Bira and Manzon crashed out of the race, ending Manzon's brilliant performance. This wouldn't be the only accident in the race.

When Luigi Fagioli's transmission failed, the oil left behind caused Paul Pietsch and Philippe Etancelin. Felice Bonetto's accident debris caused Peter Whitehead to spin out of the race. Nello Pagani tapped Alberto Ascari out of a brilliant seventh place, and Franco Rol was also bumped out by Consalvo Sanesi towards the start.

Championship contenders de Graffenried and Fangio had dismal races, quickly dropping to the very back of the pack along with Johnny Claes. All three retired with mechanical issues after doing nothing of note and relinquishing their title hopes to Serafini and Farina, who were fighting for the race lead.

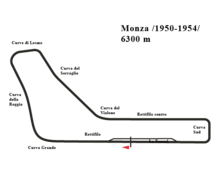

Indeed, the two Italians were well ahead of everyone else with ten laps remaining. Serafini, holding the fastest lap, simply had to keep his position to win the title. However, if he lost his fastest lap, he would lose on countback, or by one point if it was to Farina. Desperate to avoid such a situation, he decided to pull out a qualifying lap to secure that much-needed point. Unfortunately, while doing so, he lost control of the car on the entry to Curva Sud and span off. His effort to seal the title caused him to lose it.

And so, Giuseppe Farina won the race and the title, with all three other contenders ahead of him in the standings retiring from the race. Louis Chiron was left to pick up second place, while the Gordini managed to salvage a podium after Manzon's retirement. Indeed, Sanesi and Cabantous had been fighting for half the race, and tha attrition had meant that it became a fight for third place, which Sanesi won. Tazio Nuvolari came home an immensely popular fifth place, retiring on a high and securing the record for oldest Formula One points scorer at 57 years of age.

Débutants also made an impression, with Nello Pagani finishing seventh ahead of Charles Van Acker and Troy Ruttman. David Murray and Bruno Sterzi were the last finishers, quite some way back, Sterzi even finishing nine whole laps behind Farina. Quite understandbly, Sterzi never competed in another championship Grand Prix.

Classification

Entry list

Qualifying

Race

Notes

Drivers

- Only pole position for Louis Chiron.

- First podium for Consalvo Sanesi.

- Final podium for Louis Chiron.

- Final points for Louis Chiron.

- Only points for Yves Giraud-Cabantous and Tazio Nuvolari.

- First start for Nello Pagani, David Murray, Bruno Sterzi, Paul Pietsch (only start for Sterzi).

- Final start for Tazio Nuvolari.

- First entry for Nello Pagani, David Murray, Bruno Sterzi, Paul Pietsch, Francesco Godia and Franco Comotti (only entry for Sterzi, Godia and Comotti).

- Final entry for Tazio Nuvolari, Bill Holland, Raymond Sommer and Wilbur Shaw.

Constructors

- Only pole position for Maserati.

- Only points for Lancia.

- Final start for Jaguar as a chassis maker.

- Final entries and start for Jaguar and Aston Martin as independent contructors.

- Final entry and start for AAR (chassis), Weslake (engine) and Lancia.

Entrants

- Only pole for Claes Racing Developments.

- Final podium for Claes Racing Developments.

- First start for Redman Racing Team.

- Final start for Jaguar as an entrant and All American Racers.

- First entry for Redman Racing Team.

- Final entry for Kurtis Kraft, Aston Martin and Jaguar as entrants and All American Racers.

- Only entry for Nello Pagani, American Maserati and David Murray.

Laps led

- Louis Chiron: 5 laps (1-2, 4-6)

- Luigi Faigoli: 1 lap (3)

- Giuseppe Farina: 67 laps (7-13, 15-17, 24-80)

- Felice Bonetto: 1 lap (14)

- Dorino Serafini: 6 laps (18-23)

Records broken

Drivers

- Oldest pole sitter: Louis Chiron (51 years and 30 days)

- Most career starts: 13 drivers (6)

- Most career entries: 11 drivers (7)

- Tazio Nuvolari retires as oldest driver to enter, start and score points (57 years, 9 months and 18 days)

Championship standings

| Pos | Driver | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | |

| 2 | 21 (24) | |

| 3 | 20 (21) | |

| 4 | 18 (19) | |

| 5 | 15 |

- Only the top five positions are listed.

| Previous race: 1950 French Grand Prix |

Alternate Formula 1 World Championship 1950 Season |

Next race: 1951 Monaco Grand Prix |

| Previous race: None |

Italian Grand Prix | Next race: 1951 Italian Grand Prix |