1950 French Grand Prix

The 1950 French Grand Prix was the sixth race of the Formula One World championship, held on July 2nd 1950 at Reims-Gueux. The race was won by Giuseppe Farina, who took his second championship victory. Dorino Serafini finished second and took the championship lead from Juan Manuel Fangio, who finished fourth. Toulo de Graffenried finished third. The race also marked the first entry for both a female driver (Hellé Nice) and an Irish driver (Joe Kelly), though none made the start. It was also the first time that a father and his son both started the same race (Louis and Jean-Louis Rosier).

Background

With two races to go in the inaugural season of Formula 1, anyone could still win the championship. The race attendance had been top-class, but entries would be limited for 1951 to decrease grid sizes. Meanwhile, Juan Manuel Fangio still led the championship, while Dorino Serafini, who started the season on a provisional license, won his first race in Belgium, getting within one point of the Argentine in the championship, while de Graffenried, the polesitter in Great Britain, was still third. The other race winners, Farina, Mauro and Chiron, were 4th, 5th and 6th. The entry list consisted of 39 cars, but a temporary decree by the FIA limited the starting grid to 28 cars.

The main and only surprise among the three big manufacturers was Maserati, who were unable to find a fourth driver for the French Grand Prix, Jimmy Davies' license having expired after his attempt at the Belgian Grand Prix, in which he was deemed not quick enough to be awarded a second attempt. Myron Fohr, meanwhile, had a sufficient racing pedigree to be allowed two starts, and the second would come in France. Alfa Romeo had yet to find a fourth driver for their home race at Monza. The slightly shorter entry list was in part due to Scuderia Maremmana. Bill Holland was still allowed one last entry that season, and Jacques de Rham decided to leave the American's final entry to the Italian GP, the team's home race.

Bugatti had decided to launch an attempt on their home race, full of confidence, in the Bugattis prepared by ENB, but with the French constructor's own engines instead of the usual Gordinis. ENB themselves would run a single Ferrari for Jacques Swaters, whose impressive début allowed him to get a second entry this season. All American Racers were probably happy to see Harry Schell's license expire for the season, the young rookie described as a "cocky playboy who lacked commitment". They had found a rookie, Troy Ruttman, who had already competed in the Indy 500 earlier that year for EXTRAS. Ruttman would become the youngest driver ever to start a race in the World Championship (excluding the Indy 500) at just 20 years old. The aformentioned EXTRAS, after missing the Belgian GP fixing the ERA and searching for a new driver, Peter Walker's license having expired, had indeed found a new driver, David Hampshire, who had already scored multiple podiums in top-class local races.

A new team has joined the fray that weekend. Enrico Platé and the remains of the late Achille Varzi's team had surprisingly merged, and the lack of remaining top-class drivers had led the team to hire an uncertain prospect, Brian Shawe-Taylor, whose performance at Reims would determine whether or not he would be allowed to enter the Italian Grand Prix. Claes Racing Developments had again entered Claes himself and Louis Chiron. Chiron was desperate for more points after his beautiful victory at Silverstone, while Claes was still after his first points. His finish at home should have given him a good confidence boost, as he now knew what he could do through the whole race distance. He knew he had pace (he led most of the British GP before his retirement), now he had to convert it into results.

ART's lienup had remained almost unchanged since Belgium, with Manzon, Giraud-Cabantous and Sanesi set to stay on for Italy, while local driver and son of the chassis supplier Aldo Gordini made his international début. Kurtis Kraft had struck a surprise deal with Ferrari America to equip Villoresi's car with the Italian manufacturer's engine, while Stuck would keep the regular Offenhauser engine to compare performance from one engine to the other. It remained to be seen whether or not the Ferrari powerplant fit in the American chassis.

Phoenix and Jaguar's lienups had not changed one bit, apart from the latter attempting to sign Indy 500 winner Johnny Mauro, who refused to let go of his entry spot for the Italian Grand Prix. Aston Martin, meanwhile, had finally found a second driver to drive alongside Sommer. This man was Jean-Louis Rosier, who burst onto the scene in June when he won the 24h of Le Mans, driving with his father Louis. That was his first high-level motor race, and he only drove for an hour, so it remained to be seen if he really was F1 material. Motorsport Bleu's local third driver for the race was experienced sports car driver Pierre Levegh.

As usual, many privateers entered the event, including veteran woman racer Hellé Nice, who managed to scrape together enough funding to start a farewell race at 49 years old. She was the first woman ever to enter a Formula 1 race, and she wasn't likely to do so after all her sponsors left her when Louis Chiron accused her of working for the Gestapo during the War. Georges Abecassis and Joe Kelly also entered private Altas. Unknown driver and businessman Dries van der Lof was refused entry due to a lack of experience.

Race weekend

Qualifying

After Ferrari dominated qualifying in the Belgian Grand Prix, Alfa Romeo dominated qualifying in France. This time, Fangio didn’t take pole. Instead, it was Giuseppe Farina, the winner in Monaco, who would start the race from the front. Fangio would start third, just ahead of Trintignant. Myron Fohr had gained some experience compared to the last race and started a hopefully lucky 13th. Fangio and Farina were split by the Belgian GP winner Dorino Serafini, who was again the best of the Ferraris, threatening Fangio’s championship lead.

In fact, the front of the grid was so close that even though four positions separated Serafini from the next best Ferrari, driven by Reg Parnell, their best times only differed by two tenths of a second! The other Ferraris would start 8th and 9th. To finish off the top manufacturers, the Maseratis qualified 5th, 7th and 11th, with Bonetto actually beaten by Johnny Claes in the private car! It had to be said, however, that Claes’ qualifying performance was nothing short of extraordinary, as his more experienced teammate Louis Chiron only managed 18th place.

The next best private car probably made ENB regret the firing of Yves Giraud-Cabantous, who plonked the ever-improving Gordini in twelfth position, with Manzon 16th and Sanesi 22nd. Aldo Gordini, however, had a weekend to forget, his lack of experience and ultimate pace showing, as he only qualified 32nd, failing to qualify. However, three performances really stood out. At Phoenix, while Ascari managed a decent 26th place to qualify for the race, Gonzalez drove a simply stoking lap to qualify in 14th place, while Aston Martin were equally brilliant on the long French straights, qualifying 15th and 20th, with Jean-Louis Rosier having a good début.

Scuderia Maremmana made the right choice to enter only Biondetti for this race, as the Jaguar engine was obviously lacking power, though Biondetti would still start in the top 20. His goal would be to gain some feedback towards the car for the team’s home race. Meanwhile, Motorsport Bleu’s slide down the field continued. Bira set the 19th best time, and the joys of the two podiums seemed so far away. Rosier was even outqualified by his son in a theoretically inferior car, the same son who had barely driven during their victorious at Le Mans. Pierre Levegh even failed to qualify for his championship début, just half a second away from making the cut. Jacques Swaters made the right move by using his extended license to make the trip to Reims, as he qualified for the second straight time in his private Ferrari for ENB. He would start ahead of other privateers Brian Shawe-Taylor and David Hampshire, all driving for customer outfits and making their débuts in Formula 1.

Troy Ruttman also seemed to have been a good signing for AAR, as he had now become the youngest driver to qualify for a Formula 1 race, excluding the Indy 500. Staying with the American teams, Kurtis Kraft’s gamble to switch to Ferrari engines for Villoresi did not pay off at all. While Von Stuck managed to qualify the frankly very slow Offenhauser-powered car, the Italian powerplant did not go very nicely with the chassis and Villoresi was only 34th, and off the grid. Other privateers failed to qualify. Abecassis and Kelly never really had a chance to make it in an unproven and underpowered Alta, while Hellé Nice’s attempt at a farewell race ended up being stillborn, despite a quick car. Old age and, perhaps, a lack of motivation prevented her from qualifying.

Others, though, had no excuse. Jaguar had been regularly qualifying since the start of the year, but the reduced grid size should not have been a hindrance. It was, and they would watch the race from the grandstands. However, the greatest disappointment of them all had to be the works Bugatti team. Apparently, the car worked much better with a Gordini engine in it, as it was definitely not just the drivers’ fault that they ended up over 7 seconds away from pole position and three seconds from qualification. The race looked like it would be a straight fight between Alfa and Ferrari, with Maserati perhaps spoiling the fun.

Race

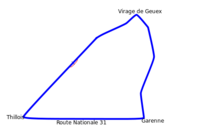

Right from the start, six drivers broke away and began battling hard: Farina, Serafini, Fangio, Taruffi, Parnell and Trintignant. Further down the field Peter Whitehead and Jean-Louis Rosier tangled at Thillois and spun into the fields, both drivers retiring on the spot. Within a few laps, de Graffenried had joined the little group, while Farina had fallen behind a little bit, leaving Taruffi, then Fangio to lead the race for a few laps. Serafini led for four laps before de Graffenried, always reminding everyone about how he took pole in Silverstone, took a durable lead on lap 13. By this point, Farina had made up the gap, and it was Fangio who was falling behind.

Farina set out to prove that his Monaco victory was no fluke, and broke away from the pack and caught up to de Graffenried by lap 25, with Serafini close behind. A titanic struggle would break out between the Alfa and the two Ferraris. On lap 27, Farina took the lead again while Serafini and de Graffenried engaged in a spirited fight for second place. On lap 26, Robert Manzon had already stuck his Gordini in a ditch, spraining his wrist, but a serious crash marked the race on lap 36. Clemente Biondetti, two laps behind the leaders, was just outside the top 10 and fighting with Sanesi, when the veteran’s Ferrari-Jaguar left the road at Gueux. His car span and struck a concrete wall at moderate speed, and was transported to hospital. He suffered two broken arms and a fractured ankle.

Meanwhile, the race continued and Farina was taking advantage of the fight to pull out a sizeable gap without putting much strain on his car. By lap 47, his advantage was such that he decided to stop pushing. At the same time, de Graffenried dropped out of the fight to conserve his tyres, leaving Sanesi 17 laps to catch Farina. At the same time, further down the field, Felice Bonetto was having a miserable race, five laps behind. This race was ended at the Virage de la Garenne, when he spun on lap 50. At the same time, Reg Parnell was attempting to lap Alberto Ascari for the third time when Bonetto span ahead of both of them. Both aimed for the same gap and collided, ending both their races.

This was to be the last event of the race, however, as Serafini was unable to catch Farina, who became the first man to win multiple Formula 1 races. De Graffenried ended up lapped by Farina, but the lead he had developed early on was so large that he was still one lap ahead of Fangio and Taruffi, who rounded out the points. The Swiss therefore finished third, his third podium of the year, also racking up his second fastest lap. Serafini’s podium, in the meantime, elevated him to 23 points, compared to Fangio’s 21, giving him the championship lead, even though their official totals were 21 and 20 (with only the best four results counted).

Classification

Entry list

- André Simon attempted to enter after the entry list had closed

Qualifying

Race

Notes

Drivers

- First pole position for Giuseppe Farina.

- First points for Piero Taruffi.

- First and only start for Brian Shawe-Taylor and Jean-Louis Rosier.

- First start for David Hampshire.

- Final start for Raymond Sommer.

- First entry for Brian Shawe-Taylor, David Hampshire, Jean-Louis Rosier, Pierre Levegh, Hellé Nice, Aldo Gordini, George Abecassis, Joe Kelly and Charles Pozzi (only entry for Nice, Abecassis and Pozzi).

Constructors

- First entry for Bugatti as an engine.

Entrants

- Final points for Officine Alfieri Maserati.

- First start for Scuderia Platé-Varzi.

- Final start for EXTRAS, Aston Martin and Kurtis Kraft as entrants.

- First entry for Scuderia Platé-Varzi, Hellé Nice, George Abecassis and Joe Kelly (only entry for Nice, Abecassis and Kelly).

Laps led

- Giuseppe Farina: 40 laps (1-2, 27-64)

- Piero Taruffi: 4 laps (3-6)

- Juan Manuel Fangio: 2 laps (7-8)

- Dorino Serafini: 4 laps (9-12)

- Toulo de Graffenried: 14 laps (13-26)

Records broken

Drivers

- Most career victories: Giuseppe Farina (2)

- Most career fastest laps: Toulo de Graffenried (2)

- Most career podiums: Toulo de Graffenried (3)

- Most career points: Dorino Serafini (23)

- Most career starts: 14 drivers (5)

- Most career entries: 11 drivers (6)

- Oldest pole setter: Giuseppe Farina (43 years, 8 months and 1 day)

Constructors

- Most fastest laps: Ferrari (3)

Championship standings

| Pos | Driver | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 (23) | |

| 2 | 20 (21) | |

| 3 | 18 (19) | |

| 4 | 16 | |

| 5 | 9 |

- Only the top five positions are listed.

| Previous race: 1950 Belgian Grand Prix |

Alternate Formula 1 World Championship 1950 Season |

Next race: 1950 Italian Grand Prix |

| Previous race: None |

French Grand Prix | Next race: 1951 French Grand Prix |